by Andreas B. Olsson

A core goal of federalism is to unite and not divide. Therefore, it would seem that a good federalist should be against secession. But federalism is also about subsidiarity and limited Lockean government. Greater unity is not the only decisive factor in whether to be for or against secession. If a local population has been wronged – and their right to decide matters that affect only them overridden egregiously and repeatedly – then a federalist ought to support secession. On the other hand, like most theories of good governance federalism has as its end goal peace – not peace at any cost but peace nonetheless. So if secession risks plunging a relatively productive and prosperous region into destructive conflict, then a federalist ought to take this as a negative in their considerations on whether to lend support.

In light of these multiple considerations, should we support current global trends towards secession? I would argue that each secessionist cause would need to be considered somewhat sui generis. With other words, there is no one simple answer to all cases. Kurdistan is not Scotland and, though closer in case, Scotland is not Catalonia. What they all do share, however, is that they are all part of a nation state. They are not seceding from what is clearly a union of separate semi-independent states but from a singular nationalist entity.

Though Scotland is technically in a union with England, Great Britain today has more the characteristics of the type of nation state established in Europe after the Thirty Years War came to an end. The 1707 Act of Union between England and Scotland finalized the process and made one of what had once been two. Great Britain no longer had two parliaments but a single legislative entity.

Only in 1998 did Scotland get its own parliament again, but with greatly restricted legislative rights. Which imperative of the federalist mind takes precedence? Is the devolution of Scotland antithetical to our mode of thinking? Or are the Scottish acting on serious grievances and reacting to infractions on a population's right to decide local issues?

To complicate the matter further, the UK remains a member of the European Union until and if Brexit is fully executed, a union that England – yes not the UK but largely England – has decided to secede from. By the same type of referendum held in Scotland whether to stay in the UK – and which preserved that union – England managed by its sheer size to determine the fate of all members of the UK within the EU.

Which leads us to yet another problem: how do we legitimately decide if secession is warranted and can proceed? Is Brexit legitimate vis a vis Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland?

The Scottish referendum seems to have been a good example for proper procedure. We can for the moment disregard whether referendums with simple majorities are sufficient. If all parties agree, the union itself and the region seeking to secede from that union, then it is their prerogative to proceed as they see fit. This is what happened in Great Britain with respect to Scottish independence. The UK Parliament consented to the referendum before it was held; the Scottish people respected the NO result once the votes were tallied. In contrast, Catalonia has been a spectacular fiasco in terms of procedure. The central Spanish government did not agree to the referendum; the referendum was held anyway; despite questionable participation in the voting process, the Catalan parliament declared independence.

Procedure aside for the moment, there is an important contrast between the two secessionist cases. Just like Scotland, Catalonia is by proxy a member of the EU. But unlike Scotland, both Spain as a whole and Catalonia are for continued membership in the union.

We have come to what I believe ought to be a very important aspect for federalist: is the secession a secession from unity as such? Is it a nationalist claim to unlimited and unchecked sovereignty? Or, is it an anti-nationalist impulse, an effort to seek more local autonomy but within a more global context with real and actionable constraints on what can be done on the world stage? If it is the latter, I would argue that a federalist can be supportive of secession. It is not a rebellion against basic constraints imposed by the greater borderless body we call humanity. It’s not a rebellion against the Parliament of All.

Catalonia still wants to remain a member of the EU, but not under the authority of Spain. Spain represents the nationalist past of Europe. It is the unfortunate child of Franco.

Both Scotland and Catalonia share a dedication to limited government but government nonetheless. Unlike England they accept being constrained by a greater body in matters that transcend their borders. Catalonia is not rebelling against unionist constraints as such but remaining in the culturally atavistic political unit called Spain with a nationalist origin.

Kurdistan is different from our two cases considered so far because it went through only in recent generations what Scotland and Catalonia went through many generations ago. Scotland has been part of the UK since 17’th century. Catalonia has been part of Spain since the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella in the 15’th century. Kurdistan in contrast fell between the crossroads of empires and never became integrated into a nationalist unit held together by anything else but brutal force until quite recently.

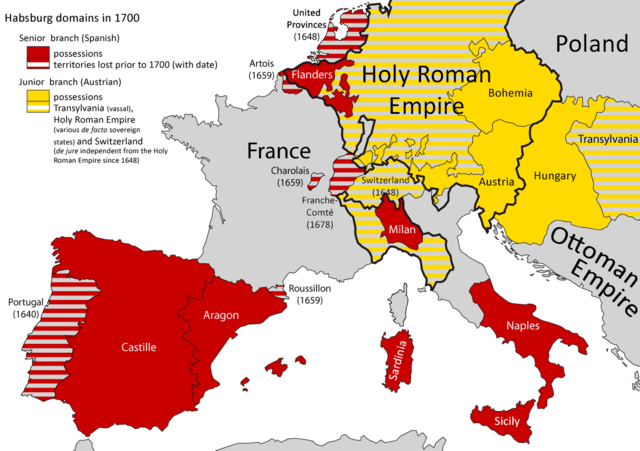

It can be argued that the empires of yore like the Hapsburg and Ottoman Empire were closer in their governance to federalist principles than the centralist nations that emerged post the Thirty Years War in Western Europe: if no harm is done beyond a region's boundary, let them play and practice as they see fit. Until industrialization obliterated even mountainous geographic boundaries and war became exponentially more asymmetrical, Kurdistan remained separate yet integrated into a wider economic good. This is after all an important purpose of federalism: global and productive peace between the individual, the state and our greater commonwealth.

Scotland’s, Catalonia’s and Kurdistan’s secessionist movements can be seen as a reaction against nationalism not a result of nationalism. I understand nationalism as an anti-imperialist reactionary force against union – the result of a poorly run Holy Roman Empire, partially justified protestation against the excesses of the Catholic church and the dissolution of empire. The functions once exercised by a vast political entity were gradually replaced by smaller states more intent on exercising strict authority over its regions as one empire after another collapsed.

In Spain the final nail in the coffin that ultimately lead to nationalism were the Nueva Planta decrees during the first two decades of the 1700’s, a unilateral abolition of regional and ancient laws contained in what were called fueros. Philip V, the first Bourbon monarch of Spain, transplanted a nationalist and centralized model of governance from France onto the Iberian peninsula. Catalonia had up until then – much like Kurdistan during and within the Ottoman Empire – been culturally separated but economically and militarily integrated into Habsburg Spain.

Around the same time as Scotland became subservient to England, Catalonia became subservient to Castile. Subservient or not, these regions benefited from European colonial conquests and an industrial revolution that completely altered European society within single human lifespans. The reward for making Castilian the language of government and forfeiting a Scottish parliament were enormous. This is especially true for Scotland that can lay some claim to being the very progenitors of the industrial revolution itself.

But despite attempts to centralize and nationalize identity, many Scots and Catalans have retained somewhat separate cultural identities. Perhaps not as separate as the Kurds but sufficiently separate to lead us to the present crisis. Their call for devolution can be seen as a reaction to the nationalist impulses still present in Spain and Great Britain.

Both Edinburgh and Barcelona were during the 18’th and 19’th century proximal to Madrid and London, the centers of vast colonial empires. During this time one would be hard pressed to see Castile and Catalonia or England and Scotland as distinct. The core us were respectively the Iberian Peninsula and the British Isles, and could be contrasted to the rest of the imperial periphery as them. This can be compared to the Roman and Socii in ancient times. After the Social War the distinction between someone who lived in the immediate vicinity of Rome versus Heraclea became largely irrelevant. Essentially, Catalonia and Scotland lived in the shadow of Castile and England, whose fights – the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War, the Mexican War, and so on – were their fights.

As the Spanish and then British empires failed, previous quirks and cultural nuances turned into sharp distinguishing contrasts. The us versus them turned inwards and divided the Scots from the English and the Catalans from the Castilians. After the Spanish Civil War, Francisco Franco brutally suppressed these rediscovered distinctions. He reasserted and nationalized identity under a Castilian flag. He banned the Catalan language from government and even media. In the name of national unity, to be Spanish was to be Castilian under Franco’s dictatorship.

The relationship between Scotland and England fared somewhat better under the democratic and parliamentary system of the United Kingdom. Perhaps this difference between Franco’s Spain and postwar Britain is the reason why Scotland’s path in determining its status has been more procedurally coherent, legitimate and emotionally contained.

Without proper procedure a federalist should not be supportive of secession unless the infractions of the larger polity against a region seeking independence are so egregious as to warrant forceful intervention by the international community. The Spain of today is not Franco’s Spain of yesteryears. It cannot reasonably be claimed that the acts of the Spanish government were sufficiently egregious prior to the referendum in Catalonia. Madrid’s treatment of Barcelona fell well within the EU standards for what is civilly and politically acceptable. Did they treat the parliament in Barcelona respectfully? Perhaps not, but they did nothing to forfeit their right to be central in determining the outcome of the Catalan question.

That said, a pro-federalist Madrid would have recognized the imbalanced and problematic past between Castile and Catalonia since Philip V and exasperated by Franco. Madrid should have negotiated a peaceful and deliberative process for the Catalans to determine whether to remain in Spain. A condition of the split should have been an EU guarantee for Catalonian membership in the European Union. Another condition should have been a solid 50% plus participation by the electorate and a substantial and enduring majority. Madrid should have been amenable to the possible and eventual dissolution of Spain as it exists today if these conditions could be guaranteed.

Such a stance by the government in Madrid would have been a clear denunciation of Spain’s ultranationalist and fascist past. It would have put Madrid on the forefront of European political evolution, a counter to Brexit and a backwards looking England mythologizing its long lost past. A stable Europe is only possible if the peoples of Europe can shed their nationalist allegiances once and for all yet retain their distinct cultural identities under a united and federated Europe. Catalonia must be given the opportunity to reassert the identity that Philip V and Franco denied them.

With Brexit imminent, I think the answer to whether or not to support a process towards Scottish independence is far simpler: Yes! England has chosen a nationalist course apart from union and the Parliament of All. Scotland must be allowed to determine its own fate in Europe. I realize that many countries in Europe may be wary of accepting breakaway regions into the union. But these countries themselves should not be fearful of devolution within their own borders, even their own dissolution. The commitment of the people of Europe should be to a united and diverse federation where culturally distinct regions can prosper, not territorial integrity based on false, antiquated and nationalist notions.

Without a union similar to the EU within the Middle East, a militarized and volatile situation and continued hostilities, the Kurdish problem is more complex and a far more dangerous issue. The federalist impulse would seem to be to first insist on securing stability. The federalist should then encourage the establishment of a pluralist union in the region committed to federalist principles and not simply stabilized by the form of dictatorial brutality deployed by the al-Assads and Saddam Hussein.

Note that tensions between Iraq and Syria over the last century does not nullify that they are part of the same cultural continuum. The collapse of the two nations in the last two decades offers an opportunity. Rather than secede, Iraqi Kurds should help solidify gains of the Syrian Democratic Forces against the Islamic State in Syria and become the progenitors of a unification of Syria and Iraq under strictly federalist principles and power sharing.

The greatest threat to the world federalist cause is not a regional assertion of greater autonomy but ultra-nationalism and anti-pluralism. No one should be allowed to secede from the Parliament of All. But to secede from a country rooted in past artificial identities and still stuck on bygone nationalist notions is legitimate. Unfortunately, there is not yet a true Parliament of All to which a seceding territory can affirm its commitment and subordinate its sovereignty.

The United Nations has not been imbued with sufficient authority to effectively arbitrate between its members except when they stand at the brink of war. And in the absence of a global legislature that can enforce the Laws of Humanity, the European Union serves as a respectable stand in. There is no reason why Catalonia should not rescind Spanish nationalism and become a member in its own right of this proxy Parliament of All, and why Scotland should not be allowed to separate from the UK and join the EU. Since there is no proxy for the Parliament of All in the Middle East it will fall on the people of that region to bootstrap it into existence from the ashes of conflict.

No comments:

Post a Comment